Botanical Casting: Where Science Meets Craft

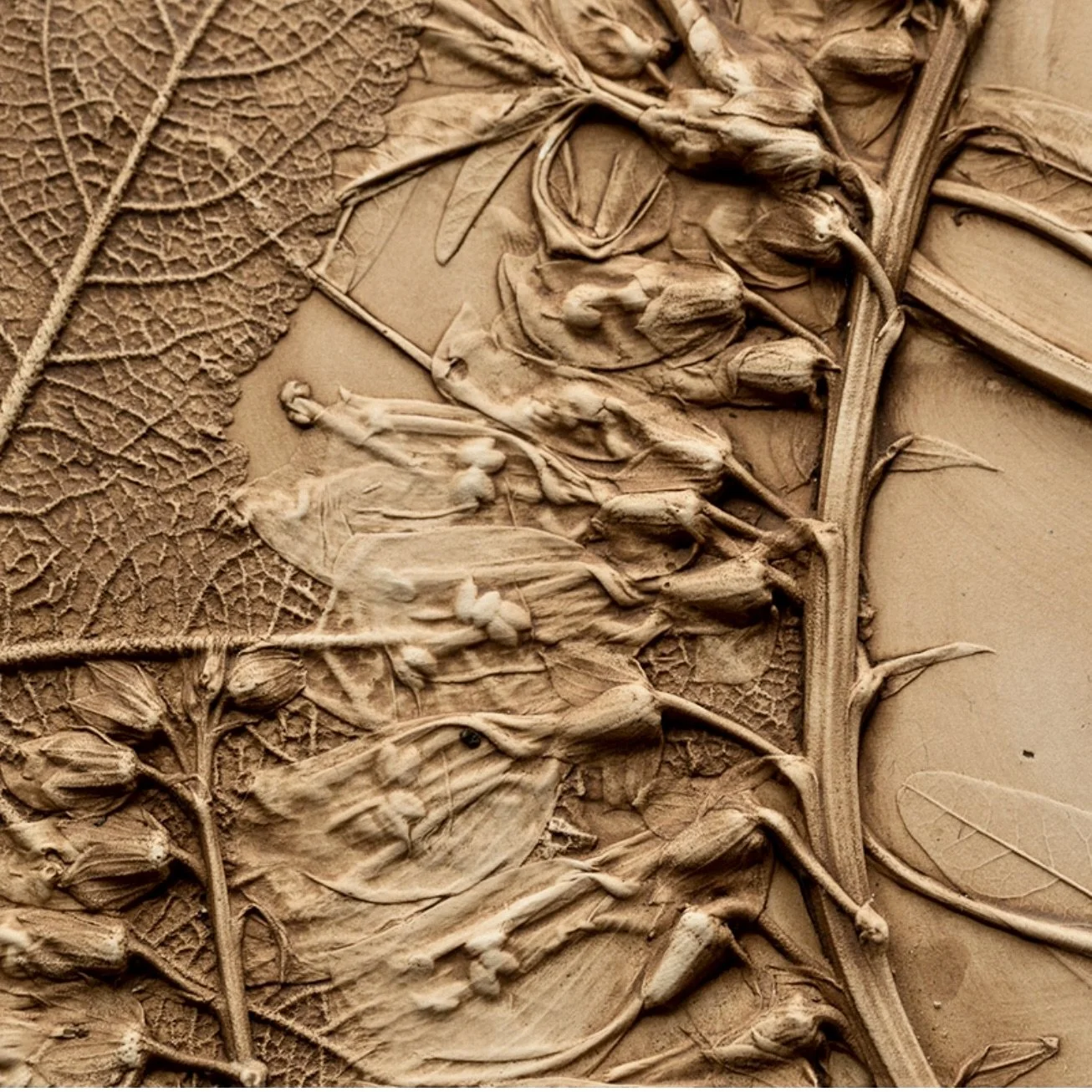

Botanical plaster plaque with natural iron oxide transferred from the clay mould, creating its warm brown tonality. As the plaster begins to dry, the surface is gently sponged back, lifting the relief and revealing highlights that accentuate the delicacy of the botanical forms.

From ancient tombs to contemporary workshop tables, botanical casting has travelled a long and quietly remarkable path. It is a practice that sits at the confluence of science and craft — serving both as a means of documentation and as a reflective, creative act — preserving the fleeting forms of leaves, stems and flowers in materials made to endure.

At Asterion & Co., we are drawn to these kinds of “quiet technologies”: methods that hold knowledge lightly, pass skills hand to hand, and allow beauty and understanding to travel across generations without spectacle or haste. Botanical casting belongs firmly within this lineage — a way of noticing, holding and translating the living world rather than attempting to perfect or control it.

Ancient roots: impressions of the living world

The earliest forms of botanical casting were often impressions rather than full sculptural replicas. In ancient Egypt, artisans pressed plants and flowers into clay or early plasters to decorate tombs, vessels and ritual objects — gestures that bound the living world to ideas of memory and permanence. In classical Greece, botanical motifs such as acanthus, laurel and vine leaves were modelled directly from nature, forming the basis of enduring architectural ornament. The Corinthian capital, with its stylised acanthus leaves, stands as a reminder that architecture itself once grew from close, tactile observation of plants.

Fine botanical details, from leaf venation to delicate petals, are captured through a layered transfer from plant to clay, and from clay to plaster.

Renaissance curiosity: Nature under study

With the Renaissance came a renewed desire to understand the natural world through both eye and hand. Botanical casting emerged alongside drawing and herbarium collecting as a means of study. Leonardo da Vinci experimented with taking impressions of leaves to examine their venation — the intricate networks that distribute moisture, nutrients and strength, and give each species its distinctive structure.

In the Medici gardens of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Florence — particularly under Cosimo I de’ Medici — plaster casts of fruits, seeds and leaves were made as artistic references and teaching aids. These objects helped bridge art, botany and anatomy, allowing texture, relief and form to be studied in ways flat images could not.

Plaster itself became central to this shift. Long used in anatomical models and architectural ornament, it was valued for its ability to capture negative space and minute surface detail with remarkable fidelity. In this context, botanical casting was not replication but translation: a moment where soft, living tissue was briefly held and then released, leaving its memory behind in mineral form.

The Enlightenment: Exactitude and exchange

By the eighteenth century, the study of plants increasingly favoured empirical observation, classification and education. In Britain, Philip Miller, long-serving head gardener of the Chelsea Physic Garden, transformed the garden into a centre for botanical exchange. Exotic plants were cultivated, compared and recorded, their forms carefully studied and disseminated.

While illustrations and herbarium sheets dominated scholarly botany, the Enlightenment emphasis on faithful structure — not merely surface appearance — laid the conceptual groundwork for botanical casting’s later resurgence. Texture, relief and volume mattered. Understanding a plant meant engaging with its three-dimensional presence, something plaster was uniquely suited to preserve.

Fragments of dried terracotta clay from earlier casting sessions, their surfaces still holding the quiet impressions of plants once pressed into them.

18th & 19th Centuries: Science, art and industry

As botany became a formal science, plaster casts found a place in classrooms and collections. They could communicate form and texture in ways pressed specimens could not. In Florence, artisans at La Specola museum produced extraordinarily lifelike wax fruits and plants — not casts in the strictest sense, but close in intent — offering durable, three-dimensional records of nature.

During the Victorian era, botanical casting flourished both as scientific practice and domestic craft. Casting ferns, leaves and flowers into plaster or metal plaques reflected the period’s fascination with cataloguing the natural world. This impulse was further energised by the Arts & Crafts movement, whose designers championed hand-made workmanship and plant-derived ornament. Botanical motifs appeared in plaster friezes, ceiling roses, tiles, textiles and metalwork, many now held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, embedding the garden quietly into the fabric of the home.

Plaster cast impressions of snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis), capturing the delicate structure of petals and stems in low relief.

20th Century: From record to expression

In the twentieth century, botanical casting loosened its ties to strict scientific documentation and moved more fully into artistic expression. Artists experimented with impressions in plaster and bronze; botanical forms appeared in jewellery, sculpture and garden ornament. The craft revival of the 1960s and 70s encouraged home makers to cast leaves in plaster or concrete for stepping stones and wall plaques.

Throughout this period, plaster retained its appeal not despite its imperfections, but because of them. Leaves tear, edges soften, air bubbles form. Each cast is contingent — shaped by timing, moisture, pressure and chance — and the losses along the way become part of the learning rather than a flaw in it.

Contemporary practice: Making, meaning and mindfulness

Today, botanical casting sits across three intertwined worlds:

Science and preservation, where casts of rare plants or fruits support museum education

Art and design, with contemporary artists casting entire leaves or seed pods at scale

Craft and wellbeing, where workshops invite participants to slow down, observe closely and make with their hands

Botanical plaster casting is also deeply seasonal. Leaves cast differently in spring than in late summer; pliability, moisture and maturity all shape the outcome. The practice rewards attentiveness to the garden and reinforces a close relationship between maker, material and moment.

Ceramic artist, Clare Mahoney exudes calm and as a tutor creates a meditative space for workshop guest to be creative.

It is within this contemporary lineage that artist, and Asterion & Co. collaborator, Clare Mahoney works. Clare’s practice is rooted in close observation and material sensitivity, using plaster to translate medicinal and wild plants into finely detailed casts that honour both botanical knowledge and the act of making itself. She has recently collaborated with the Dr Jenner Trust, casting medicinal herbs grown in the physic garden associated with Edward Jenner. These plants — once used to promote wellness and treat common ailments — reveal extraordinary textures when held in plaster, offering a tactile bridge between historic medicine and contemporary craft.

Botanical casting at The Old Vicarage

To bring this lineage into the present, we are delighted to be hosting two one-day botanical casting masterclasses led by Clare here at The Old Vicarage. Drawing on fresh plant material from the garden, these workshops invite participants to learn traditional plaster casting techniques while exploring the subtle translations that occur between living form and mineral record.

The masterclasses will take place on Saturday 9 May 2026 and Wednesday 17 June 2026, running from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm. Set within the rhythms of the house and garden, each day offers time to slow down, observe closely, and leave with casts that carry both botanical detail and the memory of making.

Workshop guests in action, rolling out clay tablets and thoughtfully arranging botanical compositions — a slow, hands-on process that invites observation, touch and a quiet attentiveness to form, texture and natural rhythm.

In short

Botanical casting began as an ancient artistic technique, evolved into a Renaissance scientific tool, flourished in Victorian craft and design, and today enjoys a revival as both art form and mindful practice. In our workshops at The Old Vicarage, we are proud to continue this lineage — inviting people to pause, to notice, and to create something lasting from the fleeting beauty of the garden.

Plaster remains compelling not because it is perfect, but because it records the hand, the moment and the making. In holding the trace of a leaf, it holds time itself — briefly stilled, carefully honoured, and quietly shared.